A so-called gradual reduction process using iron or porcelain rollers replaced the old stone burrs, and after 1890 fewer and bigger mills became the rule.

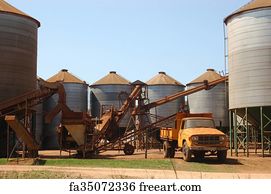

Hard winter wheat, especially Turkey Red, became the small grain of choice on the Kansas plains, and milling technology adapted to the change. This practice of mixing grains together made for a more uniform product and a more efficient method of payment.ĭuring the 1880s, another "revolution" transformed the industry. The grain for this flour came from storage bins or elevators that had been filled with the produce of many different farms. With storage facilities in the form of elevators available by the 1870s, most millers simply purchased raw wheat from farmers or took it in exchange for a predetermined quantity of flour. Soon, however, grain elevators changed the relationship between the farmer and the miller. Either way, after the miller finished his work, the farmer went home with flour or meal ground from the grain he had produced. The miller kept a percentage of the flour as payment for his service and returned the remainder to the farmer, or simply charged a flat fee of perhaps 25 cents per bushel. Splitlog and other early millers usually operated on a "custom" or toll basis. By the 1880s Kansas communities reported the existence of 350 mills with one-third of them powered by water and nearly all the rest by steam. A few even experimented with wind as their power source. Other millers were soon using steam engines to power their equipment. Splitlog and some other early millers used water power to turn the stone burrs, which then ground the corn and wheat kernels into meal or flour. Perhaps the first flour, or grist mill was established and operated near present Kansas City by Matthias Splitlog, a Wyandotte, about 1852. Although the lumber industry quickly declined in importance, flour milling became one of the state's leading industries. Th e first millers in Kansas often operated both grist and lumber mills. By the mid-1880s flour and feed milling had become the state's leading industry, and grain storage facilities (such as grain elevators) dotted the Kansas landscape, becoming a symbol of the state's abundant harvest and agricultural vitality. All this grain required grinding before it could be used, however, so early on small Kansas grain/grist mills were built to serve the needs of local communities. For most of the 20th century, wheat has been the lead product in the state's agricultural economy.

Throughout its history, the Sunflower State has been known for producing wheat, corn and other grains.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)